In outdoor product design, soft goods are changing the way we think about movement for outdoor performance. The way our bodies move is more than a single action. it’s an ongoing and dynamic process—a conversation between the body, the environment, and the gear we carry.

Whether you’re hiking rough trails, adjusting your straps mid-walk, setting up camp, or navigating a city, every small motion tells us something. The body is asking for support, and good design should respond. As soft goods designers, we understand these movements and study the interaction between the human and the products they wear and carry. In recent years, soft goods—like backpacks, wearable gear, and modular carry systems—have begun to challenge the old idea that “hard equals safe.” These products are no longer built to be stiff and rigid. Instead, they are designed to move with the body, to adapt in real time, and to feel like a natural part of us. This shift doesn’t reduce performance—it changes how we define it. Performance today means adapting to movement, supporting dynamic actions, and keeping us comfortable across changing situations combined with ease of use. This article explores how soft goods in outdoor performance are reshaping gear to better support how we move.

Soft Doesn’t Mean Weak—It Means Smart

Soft materials are not weaker. They’re more nuanced. In outdoor soft goods, fabrics like ripstop nylon, waxed canvas, X-Pac, spacer mesh, and soft shell textiles aren’t just about coverage—they enable movement, compression, ventilation, and adaptability.

Compared to hard materials like ABS plastic or rigid foams, soft product design offers more breathability, compressibility, and responsiveness. For sports product design—trail running, climbing, or mountain biking—this translates to reduced fatigue and more natural alignment with the body. When the Interwoven Design soft goods team worked with Shark/Ninja on the design for the Frost Vault Soft Cooler, we created a soft goods strap prototypes that improved user comfort and interaction. The soft structure adapts to shifting weight and varied terrain, giving users comfort and agility without sacrificing durability.

Body-First Design: A Dynamic Ergonomics

At Interwoven Design, we call this approach “body-first design.” It’s a core principle that guides how we develop soft goods across industries—but it’s especially critical in outdoor performance. Traditional ergonomics often focuses on static posture or ideal alignment. But when you’re hiking, climbing, crouching, or transitioning between urban and natural environments, what the body really needs is flexibility, freedom, and real-time responsiveness. This is where soft goods design can make the biggest impact—by allowing the product to adapt to the user, not the other way around.

Soft goods outdoor performance products are built to move with us. Think shoulder straps that naturally rotate and contour with your shape instead of fighting against it. We applied this thinking in our work with HeroWear’s Apex 2 exosuit, designing padded straps and soft interfaces that reduce pressure points and accommodate shoulder rotation, ensuring all-day wearability for users engaged in repetitive movement and lifting. The harness flexes without bunching and adjusts easily to fit a wide range of body types—an essential feature in any gear meant for motion.

Waist packs are another area where body-first design shines. In our collaboration with White Cloud Medical, we developed a soft goods waist pack for their wearable wound care system. It was designed to securely house a medical device while allowing users to bend, sit, or shift their weight without discomfort or slippage. The soft structure conforms to the lower back and hips, using strategically placed foam zones and breathable mesh to maintain stability without sacrificing comfort—mirroring the dynamic adaptability you’d expect in a trail running or trekking belt.

Back panels also matter. In our work with Saber, we helped develop a lightweight and flexible exosuit that assists soldiers with moving heavy loads, where the back interface needed to support both agility and load-bearing performance in extreme conditions. The back panel was constructed with contoured foam, airflow channels, and an adaptable frame sheet, all layered under soft but durable outer textiles. These components worked together to mold to the user’s back, distribute weight evenly, and reduce fatigue during long missions—providing the kind of responsive support critical in both combat and outdoor expedition scenarios.

The Perci Emergency Preparedness Vest that we developed for Invicta Ready, takes this philosophy into urban contexts. Designed to help families be ready for natural disasters as a quick grab and go tool, it features a modular system of pockets and zones tailored to the store critical equipment needed in an emergency while no inhibiting the motion of the upper body. Each element was placed to balance weight while avoiding key flexion points like the shoulders and underarms, allowing wearers to reach, twist, and carry without restriction.

In all of these examples, subtle design decisions—curved seams, flexible materials, layered zones—add up to a dramatic improvement in comfort, usability, and performance. This is what we mean by body-first design: a commitment to soft goods that move with you, not against you.

Beyond the Trail: Lessons from Outdoor to Medical Soft Goods

What we learn from the trail informs other areas where motion matters—especially in healthcare and wellness design. Medical soft goods must also move with the body, respond to user feedback, and adapt to changing conditions.

Take the Breg CrossRunner™ Soft Knee Brace. Though not an outdoor product, it demonstrates how principles from soft goods outdoor design translate to medical wearables. We worked with Breg to combine modular support with breathable Breathefit™ stretch fabric and Airmesh® zones for ventilation. The adjustable hinge system lets users tailor their range of motion, providing support without restricting freedom—just like in performance-oriented outdoor gear.

In both cases, we’re solving the same challenge: designing for bodies in motion.

The Future of Soft Goods Prototyping: Material Meets Movement

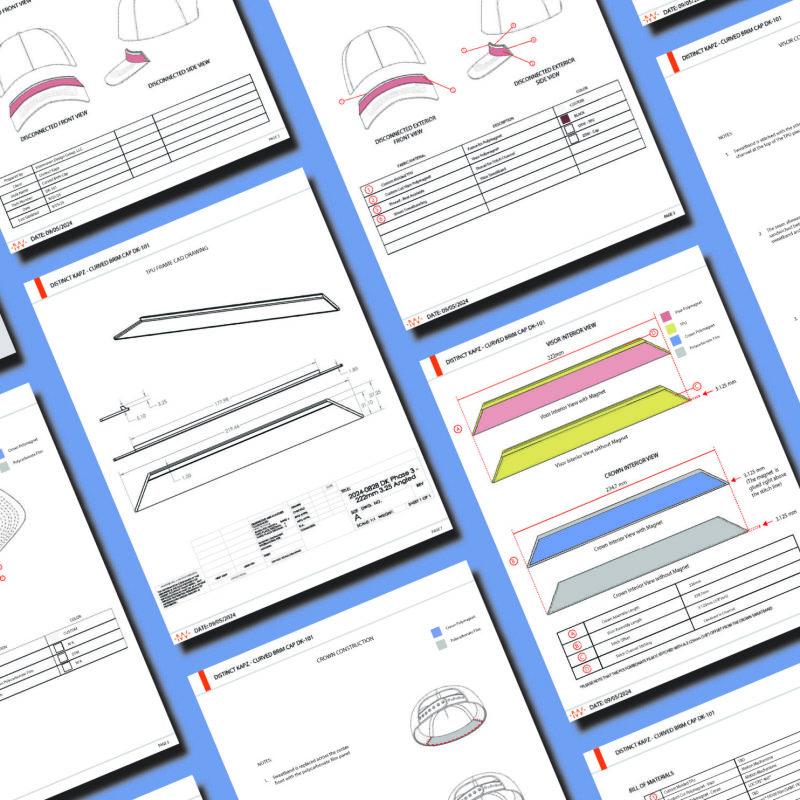

The rise of soft goods prototyping has unlocked a new frontier in performance product development. Today’s soft goods designers must go beyond creating surface forms—they must understand how every layer, stitch, and seam behaves under real-world conditions. It’s no longer enough to build a shell that looks good. Soft product design demands an iterative process of testing, refinement, and material engineering—guided not just by aesthetics, but by how the product moves with the body over time.

At Interwoven Design Group, we approach soft goods prototyping through progressive fidelity. We start with quick mockups—cut-and-sew foam, muslin, and low-cost textiles—to evaluate scale, placement, and range of motion. These early models help us identify design issues and ergonomic conflicts quickly. As the concept evolves, we move into digital patterning, custom material selection, and full-scale physical builds that test dynamic fit, load management, and wear resistance. For complex systems like outdoor soft goods and medical soft goods, this phase is critical to ensure durability without compromising comfort or flexibility.

In a recent internal concept study, we explored how combining 3D sandwich mesh with multi-zone sewing templates could deliver a high-performance pack system. Our goal was to optimize three conflicting performance needs—water resistance, targeted stretch, and long-wear breathability—while keeping the product suitable for mass production. Through layered material construction and strategic paneling, we were able to achieve localized compression in some areas, flexible articulation in others, and vented airflow across the spine. The result was a prototype that moved in sync with the body, responded to environmental shifts, and met the standards of scalable manufacturing.

This kind of hybrid thinking—blending digital design tools, soft goods construction methods, and performance testing protocols—is essential to what we call craft-forward innovation. It’s not just about making something look sleek or futuristic; it’s about knowing how textiles behave in motion, how seams influence structure, and how users physically interact with the product hour after hour. This approach helps us build smarter, more resilient outdoor soft goods, sports product designs, and medical wearables that align with real human needs—not theoretical assumptions.

By designing in layers and working across both digital and analog prototyping, we make sure that the products we develop don’t just function—they feel right. From backpacks and vests to wearable medical systems, every decision in soft goods design has a ripple effect on how people move, feel, and perform. Our prototyping methods make those connections visible and actionable, laying the foundation for soft goods that are technically sound, user-centered, and ready for real-world use.design itself.

Final Thoughts: Movement Is the Measure of Meaning

At Interwoven Design Group, we believe that soft goods design is where performance meets empathy. Whether you’re scaling a ridge, navigating a commute, or recovering from injury, soft goods should support—not dictate—how you move. As soft goods designers, we don’t just make gear. We create systems that listen, flex, and evolve with the user.

From outdoor gear to medical soft goods and wellness wearables, designing for motion is not just a method—it’s a mindset. One that values flexibility over force, collaboration over control, and experience over assumption.

We look forward to working with makers, researchers, and brands to shape the next generation of soft goods—smarter, more adaptive, and deeply human.

—

Check out the rest of our Insight series to learn more about the design industry. Sign up for our newsletter and follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn for design news, multi-media recommendations, and to learn more about product design and development!