A Q&A with Design Maven Linda Celentano

Spotlight articles shine a light on designers we admire, asking leaders in the field about their work and their design journey. In this interview, we spoke with renowned industrial designer Linda Celentano. Based in New York, Linda has built a remarkable career spanning many decades and disciplines, creating work for iconic brands like Nambé, Smart Design, Knoll, Alessi, Dansk, and Rosenthal.

A graduate of Pratt Institute and a longtime professor of Industrial Design there, Linda studied under legendary educators Rowena Reed Kostellow, Dr. William Fogler, and Gerald Gulotta. Her work is defined by its elegance, clarity, and human-centered innovation. She is famous for designing everyday objects that invite interaction and reflect her belief that “good design beckons the human touch.” She has been awarded many prestigious design awards and her work is part of the permanent collections at The Cooper-Hewitt National Museum of Design and The Chicago Athenaeum. We asked her about defining moments as a designer, continuing to push creative boundaries after decades in the industry, and the experience of collaborating with young designers.

Q:

How did you become an industrial designer?

A:

I woke up one day as a student and I learned that real people design yoyos and church interiors and everything. Wow, that was such a wakeup moment. My father was a mold maker for injection mold-making. He made steel molds for companies like Chanel and Donna Karan. It’s so fascinating when you’re a kid, anything your parents do is compelling. He would come home when I was 5 years old with stuff from work and we were always so impressed. We had no idea what he was talking about, it was just a chance to hang out with dad and see what he does when he goes to work. So, I’ve been around people that work with their hands a lot. There are a lot of engineers and teachers in my family and they all had an influence on me.

I loved playing in the woods, making little houses in the field, making and building things. When I got to Pratt, I learned that there was a way to actually make things three-dimensionally that were real products for the world. I became fascinated with art and industry. Making one-of-a-kind things just didn’t tickle my fancy.

Q:

You’ve had a remarkable career designing for brands like Nambé, Alessi, and Knoll. Looking back, what are the defining moments that shaped you as a designer?

A:

One of the most defining moments for me was working in a factory. I was designing, but I was also in a factory environment. I encourage my students to work in a factory as a summer job. The miracle of manufacturing becomes a reality once you see products being prototyped, manufactured, and going through quality control. You get to see the whole process from beginning to end. It is about process, not just the event of a produced final product. Once you understand working in the factory environment, you understand manufacturing all over, in all realms. The factory was out here in Passaic, New Jersey, and we manufactured products for orthopedic surgery. I spent a lot of time in the operating room, observing surgical procedures and then I went back into the factory and worked with the men and women in the shop where we develop prototypes. I would run down to Canal Street and get pieces of wood, plastic or foam or metal or whatever and bring them back to mock something up first.

What was so cool was that once you three-dimensionalized the idea, you could jump into the computer, start creating the manufacturing drawings, bring that to the prototype department, and start getting things actually made. It’s all experimentation until it gets to the assembly line. That’s seeing something come to fruition. The assembly line thing gets me every time.

Another defining moment was, as a child, seeing the table being set every day for each meal—going through that ceremony of choosing settings for the table. That was an important design experience. Seeing cooking and everything involved, and seeing my parents treasure something beautiful would really capture my attention; seeing that moment that they would admire something. After washing a glass, they would hold it up to the light to see the clear crystal. Moments like that were so important.

Q:

Many of your designs have become iconic design objects. Could you share the story of one that is particularly meaningful to you?

A:

One of my favorite stories is from when I was designing for Nambé. I love designing initially in three-dimensions. So, I bought a lathe and I dragged it up to my old apartment and put it in the dining room—because that’s the only place I had for it—and turned candlesticks on the lathe in my dining room. There were chips and material all over the place! It was so funny but, for the sake of good design, it was worth upsetting my whole home. I just love that, to be young and kind of nuts. It was exciting, and they went on to be very successful designs.

I remember coming from a meeting from Dansk one day with my business partner, Lisa Smith, and everything went poorly. Nothing went right. So we’re in the elevator and we’re complaining about how the meeting went, and there was some guy in the elevator. We’re carrying our bags and everything, our goods, and he looks at us and he says, I’ll look at your work. It turns out that he was the marketing director for Nambé and that little complaining session led us into a 30-year working relationship with a client. So, you never know how things can come together.

Q:

Your work embodies abstraction, elegance, and innovation. How do you continue to push creative boundaries after years in the industry?

A:

I love working experimentally and coming up with new designs, whether it’s in glass or metal or ceramic or whatever material. When you’re working experimentally, boy, you just don’t know if it’s going to sell. You have to hit it right with marketing and everything that’s going on in the world and what people are looking for. You may be showing the most beautiful thing in the world and if it’s not fitting into the marketing plan, then you have to move on.

I depend very much on my colleagues, particularly Karen Stone, Jeff Kapec, Deb Johnson, Lisa Smith, and Gina Caspi. I’m forever running designs by them to get feedback. This experience is dear to me because I really value their feedback and opinions. I will also run things by Bruce Hannah and Tucker Viemeister, and they’re very patient with me. I work by myself and I hire freelancers, so getting that feedback is really critical as well.

Q:

You’ve said that “good design beckons the human touch.” Can you elaborate on that?

A:

As a child, I was always drawn to the warmth and kindness of others. Design is wanting to be close to the things you love. It’s that simple.

Q:

How has your design philosophy evolved over the years? What principles have remained unchanged?

A:

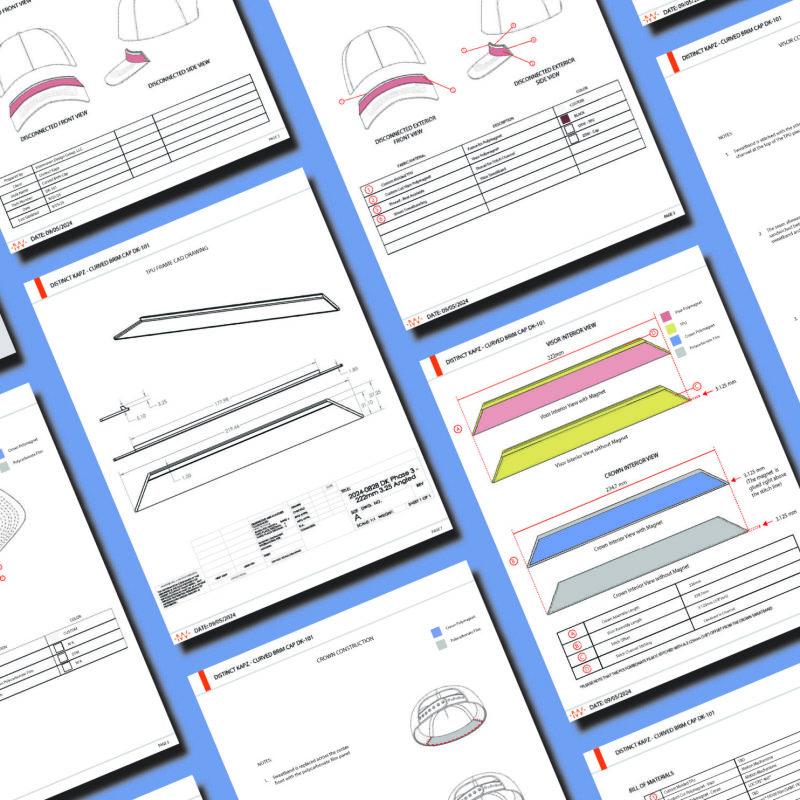

In the beginning, we would start things three-dimensionally and really develop them in three dimensions. The things we came up with to make things three-dimensional were quite remarkable, we didn’t have the advantages of all these computer programs to make something feel real even before it was a product. Back then we were working conceptually in three dimensions: plaster-spinning, making things out of wood, cardboard, spackle, museum board, ceramic, plastic, so many different materials. We did pencil drawings of everything that we needed to manufacture. And then, eventually, we were working on the computer, which was amazing. Today the computer gets us to so many interesting levels as far as manufacturing, marketing, and being able to show beautiful renderings. What’s essential for me is to have a 2D/3D/2D/3D process. I’ll come up with a doodle or a ceramic shape or a clay form and then I’ll work with my freelancers. I’m certified in Solidworks but I remember Gina Caspi telling me, “Linda, you can’t be excellent at everything. Why not just be a 10 at the things you’re good at and then hire people that are all 10s.” That was some of the best advice I was ever given by Gina.

Now I work with young, up-and-coming designers. We draw up the design in Solidworks and then we get a 3D print. I see the 3D print, which is half scale, and I’ll make my markings on it to note the changes. Then we’ll go back to the computer, improve the model, do another 3D print, take another look, make improvements, and so on. So, it’s a 2D/3D thing. Ultimately, after everything’s refined, you get a full scale 3D print.

When you do the first Solidworks model and pop it into a keyshot rendering, it’s so powerful. The client sees that and they say, Let’s do it! Let’s make a sample right away! And I have to tell them, No, we really need to backtrack and make these smaller refinements before we can go ahead and make a sample. There’s so much process work that needs to be done on the road to that goal. So, how things have changed is that you have to work with the computer and with people and go back and forth. Once again, design is a process, not an event.

Q:

If you could go back and give advice to yourself as a young designer, what would you say?

A:

I would say that it’s okay to be an introvert. The world is full of extroverted people. Susan Cain, who wrote the book Quiet, said that introverts are many of the real workhorses of the world. It’s good to have an understanding of this, within yourself and with others, that it’s okay to be an introvert. Why try to make an introvert into an extrovert? On a scale of one to ten, I’m a four or five, on average. But, over the course of my day, I might be a one, a two, a three, a nine, a seven, a six, and then a five. I try to encourage students to be okay with where they’re at for the day and for the moment.

Q:

What excites you most about working with younger designers, and what challenges come with it?

A:

Old school and new school. It’s so exciting to work with young designers. It can be sad, though, for some old school designers. They’ve had to hang up their slippers because they don’t have the technology to support themselves any longer. They know how to make things by hand. They know how to turn things on the lathe but they don’t have the technology. I feel that teaming up with young people who have that technology makes for a great team between old school and new school. And I work exclusively with young people. I learn from them and they learn from me. I work with my team at home here in my studio, over Zoom. I am texting them or I’m on my iPad, sending them doodles, 2D and 3D drawings, or photographs. We pull up Solidworks, and they will model the idea.

We’ll be designing something and I’ll use Rowan Reed Kostellow’s principles and language. They, too, are from Pratt, so they also know Rowena’s principles and language. It is not just about looking at something and saying, I like it. I don’t like it as much. It’s not good enough. Rowena taught us the language of three-dimensional literacy. So the two of us will be looking at the work and I’ll say, You need to make the concave and negative space of the volume of the form deeper to improve the overall proportion. Or, The curve on the spline needs to be a faster curve with more accents towards the end of the curve. Or, the negative volume could be more horizontal instead of vertical, so it relates better to the other objects in terms of the overall proportions. This kind of language. I encourage all designers and design students to read Rowena’s book, Elements of Design, to take workshops with us at The Rowena Group, to follow our newsletter, and to follow us on Instagram. I want them to understand that being able to communicate in three dimensions with real language is the way to go today. It creates so much freedom. The freelancer I’m working with completely understands everything I’m talking about. I could talk to anyone who’s a designer from anywhere in the world and they would understand. Anybody can understand that language, if they really listen to it, but not everyone can speak the language. Pratt students, when they get out there, they really sound like geniuses. Learn a new language!

Of course, you are not only speaking to other designers. You might be working with marketing, and they might have a background in art history or some creative field that led them there, giving them some kind of visual understanding of things. To be able to say things like, That space should be more concave so the liquid can flow more, right now it’s too shallow, that’s valuable. To be able to describe the qualities of a design with someone outside the design team while using this language is really important, too. Certainly in terms of working with people in quality control in the factory. The language is beautiful. It’s not just something that you do in class.

Q:

Can you share a time when collaborating with a younger designer changed your perspective?

A:

There are many examples, but I’ll mention one. I was working on a deadline. There were a couple of us working on the project and we sprayed a large print of a render to lay it onto a board. When it went down onto the board it didn’t lay flat and I nearly lost my mind. No! What are we going to do! I’ll never forget what the young student said. He said, “There’s always a way.” And he managed to undo it, lay it down flat, and it was perfect and everything was fine. Whenever I run into a problem or a challenge like that, I hear his voice and I think, There’s always a way.

Q:

How can emerging designers best leverage the wisdom of design veterans while still asserting their own vision?

A:

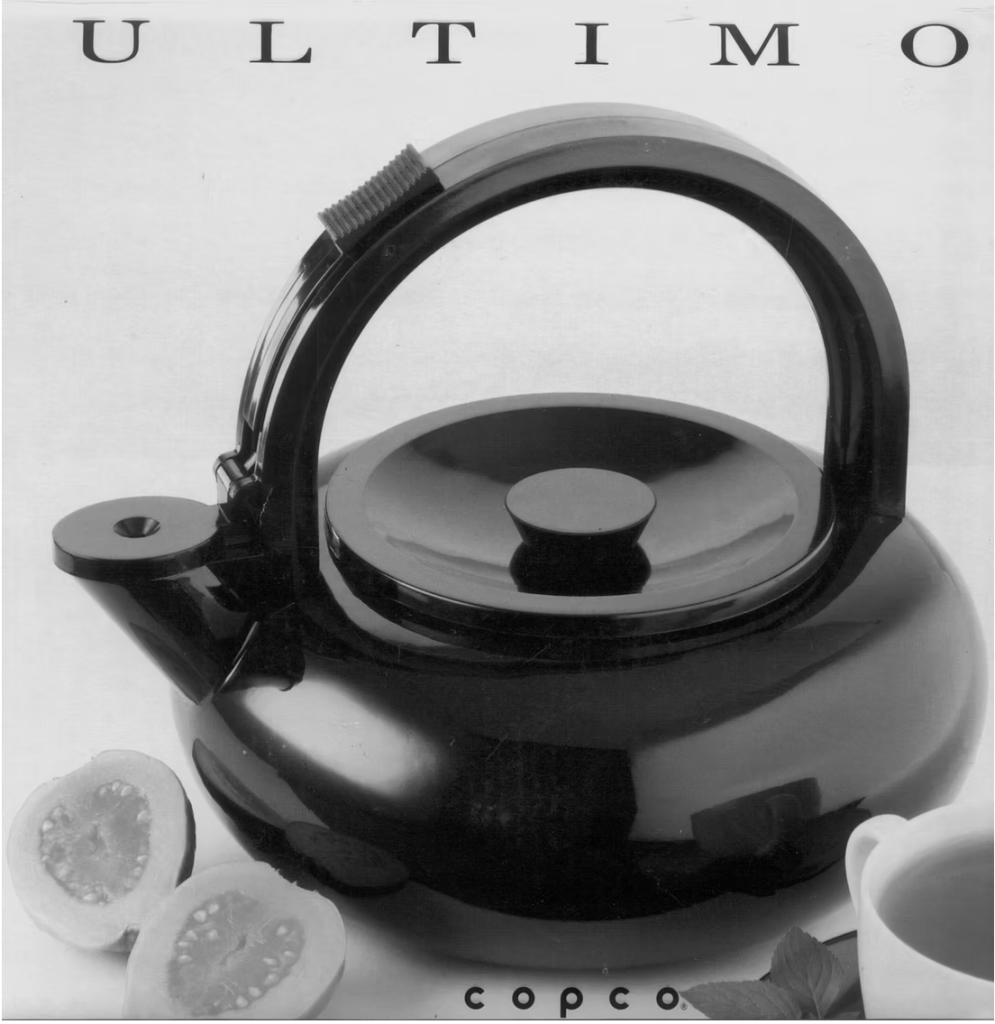

You’ve got to be working with people that are open-minded and let people in. I try with my freelancers to really hear them, what they have to contribute. I love being able to say, What do you think is best? Or, How do you see this going? Or, What do you think is better, transparent or opaque? Which do you like better? I love getting their feedback. They’re visual people, just like I am. It’s a gift to be able to work in a team setting, not only because of their incredible skills but because of what we have in common. When I was a senior at Pratt I was working with Sam Lebowitz. He taught me so many things. He taught me the difference between a 32nd of an inch and a 16th of an inch. When I designed eyewear, boy, that became really important. I designed a whistling tea kettle for Copco with him. I was just a senior in college, and here we were. He gave me so much leeway. It was wonderful. That tea kettle was a great seller for over 25 years, which is almost unheard of in housewares unless you are an OXO product!

Q:

What are the most significant shifts you’ve seen in the design industry over the course of your career?

A:

Everything changed with computers and digital work. Everything changed dramatically, and definitely for the better. But I’m worried that many things are being designed for a Keyshot render. It’s unbelievable. I have a Calphalon coffee pot. It makes no sense. I have to open the lid this way to pour the water over the top of the lid. It’s all backwards and crazy. And then the filter paper holder is not tall enough, so when you swivel the cone shaped paper it gets all jammed up and the water doesn’t drip through it properly. I had to work with it . Reason why I didn’t return it is because the quality of the coffee it made was good.

On the other hand, when I went to Turkey, I was in a museum and I saw a pair of boots that were gorgeous. They were handmade and they were so beautiful. There’s no way they could have been designed on a computer. They were designed on the foot, there’s no question about it. We can’t lose the old ways but we also can’t deny ourselves the advantages of modernism.

Q:

Many industries experience ageism—have you faced this in design? How do you think the industry can better value experience?

A:

Ageism is a serious problem. For me personally… people open the doors more for me now as I’ve gotten older. Gray hair will encourage that! I haven’t really experienced it in my life other than the beautiful experience of hearing someone like Patricia Moore talk about how we don’t say the word ‘elderly’, we say ‘elders’. There’s such beautiful meaning in the wording that she uses in terms of human beings. There used to be a bench near the elevator in Pratt Studios and they took it away. I don’t know why, but that elevator is quite slow and it was so nice having a bench there. I remember Lenny Bacich used to say, Try being human. He, along with Rowena, Dr. Fogler, Gerry Gulotta, Ralph Applebaum, Lenny Bacich, they were all mentors and friends, and they spoke their wisdom!

Q:

What do you think separates a good designer from a great one, especially after decades in the field?

A:

Some designers are trainable and others have raw talent. Great designers are both. Maybe I could substitute the word ‘training’ for ‘designers who know how to educate themselves’ because it’s all a learning process. It’s all a process from beginning to end, and understanding that, once again, it is a process and not an event. Keyshot is an event. The process of designing something is an educational process. It comes along with being inspired, getting good feedback, and exploring; pulling in years and years of training and then being as open as a child when you first design something. I can be stubborn at times, but I definitely still get into that child-state when I’m designing.

Bill Fogler, when he was ill with terminal illness, asked me to take over his class. That was the hardest experience I ever went through; going through his illness with him. He taught for 35 years. I said, “How can I fill your shoes? That would be impossible.” And he turned to me and said, “Linda, all you have to do is love them.” And that’s all you have to do with people in life, just love them. Students especially, because they’re really struggling. They’re really trying to make it work and make it happen. If you approach them with that kind of care and openness, it’s a wonderful thing. There are times you just want to shake them! Every time I want to shake them a little bit I think, No, no, that’s not the right approach.

Q:

Do you see a generational divide in design thinking, or do core design principles remain universal?

A:

I’m experiencing people being drawn to each other because of their common interests. It’s like writing a good script. It takes time, you’re crafting it from the beginning, and there are so many players involved. It’s like a good dance performance, right? Everyone’s in relation to one another. I don’t think I ever feel like, Those young kids, what do they know? It’s time to really applaud the youth in the world. They have so much to give and they’re incredibly optimistic. Thanks to them, I feel a lot of hope for the future.

I do that in my own little world on a local level. I can change the world in my day-to-day thinking and exchanges with people, whether it’s talking to my mom or my neighbors or my client—just taking a real interest in them and in what’s going on in my world; living more in the present, in the moment. If everyone lived their life fully in a local way , society would be a better place. Someone said to me recently, When you’re on the phone, and someone’s just said something that interests you or pleases you, smile. Don’t save that for an audience. Try to capture more joy in your life.

I think it’s important to encourage the youth. Don’t break their spirit. There are times when we just need to know that we’ve been listened to. A young person is so amazed when you ask them about themselves. There is a family that lives across the street from me and the young son just applied for colleges. I helped him with some of his applications, and his whole world opened up when he knew I was there for him. There are different speeds to how people respond to things in life. I think of my grandfather so often, of him just nodding and saying, Show me more. He had very few words to respond to me as a young kid. There was more of an outpour from me because his interests were so broad and he wasn’t judgmental. There is a great generational divide if we’re not open-minded. No matter where we are, no matter how old we are, no matter what generation we are, we need to be open-minded.

—

Check out the rest of our Spotlight series to hear more from leaders in the design industry. Sign up for our newsletter and follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn for design news, multi-media recommendations, and to learn more about product design and development!