A Q&A with Soft Goods Designer Anthony Parrucci

For this installment of our Spotlight series, we caught up with former Interwoven Design Group designer Anthony Parrucci, now a Soft Goods Designer at Newell Brands in Atlanta. From his early days dreaming of designing hockey gear to building innovative products for the baby industry, Anthony has carved a path defined by curiosity, collaboration, and a deep respect for hands-on making. In this conversation with Interwoven founder Rebeccah Pailes-Friedman, he reflects on conceptual prototyping, the power of “sketching in 3D,” and how early models can unlock new insights into user interaction and scale.

Anthony earned his master’s degree in Industrial Design from Rochester Institute of Technology after completing undergraduate studies in Business Administration and Art at Elmira College. Before joining Newell Brands, he spent three years at Interwoven Design Group, where he helped develop products across the athletic, medical, and military sectors—ranging from exoskeleton suits to technical bags and soft goods. His approach blends material experimentation with a strong focus on real-world usability. Outside the studio, Anthony brings the same discipline and drive he once applied to ice hockey, which he played at the professional and collegiate levels. Whether on the rink or in the workshop, he’s always been drawn to how performance, form, and human connection intersect.

Q:

Tell us a little bit about your background and how you found your way into industrial design.

A:

As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a hockey player. That was the dream. But what I found most exciting was the equipment—sticks, pads, helmets—and the idea of designing it myself. I knew I wanted to be the person behind the gear, making things better for athletes. But the funny thing was, while everyone could tell me how to become a pro hockey player, no one had any clue how to become a product designer. I kept asking, but nobody could point me in the right direction.

It wasn’t until undergrad that I met a professor who changed everything. He helped me find the path and really took me under his wing. I went to RIT, studied industrial design, and honed my skills while finishing up my hockey career. After graduation, I interned at Interwoven, and that turned into a full-time job—which was honestly one of the best places to grow as a young designer. I spent about three years there, getting my hands dirty, building fast mockups, and learning how to make ideas real. Now, I’m working at Newell Brands as a soft goods designer, focusing on the baby space. It’s a change of pace from Interwoven—bigger team, different structure—but the fundamentals of good design still apply.

Q:

What does conceptual prototyping mean to you, and what role does it play in your process?

A:

To me, conceptual prototyping is one of the most important parts of product design—especially when you’re working on the front end of a project. In fast-paced environments, having a way to quickly explore and communicate ideas is everything. I remember when I was in school, I was so hesitant to make mockups. I worried that if something was built with cardboard or hot glue, people would judge it. I’d think, “This muslin has raw edges—are they going to take it seriously?” It took me a while to realize that the point of those early models isn’t perfection—it’s validation. You’re trying to test an idea, not deliver a polished object.

Once you get over that mental hurdle and stop caring about fidelity, you’re limitless. You can make a crude mockup and say, “Imagine this part holds electronics,” and suddenly you’re in a conversation about function, user interaction, and viability. At Interwoven, that was a big part of the culture. You could build something messy, cheap, fast—and the point was to learn. It wasn’t about impressing people with how pretty something looked; it was about getting information quickly, failing fast, and saving money in the process.

Sometimes a $1 muslin model tells you more than a $300 3D print. That’s the ROI of prototyping. Even though there’s no exact formula for it, you learn so much by making something tangible. And that knowledge pays off tenfold when you move to the next stage.

Q:

At Interwoven Design, we often talk about “sketching in 3D.” How do you think 3D prototyping compares to 2D sketching in your process? When do you choose one over the other—or do you use both?

A:

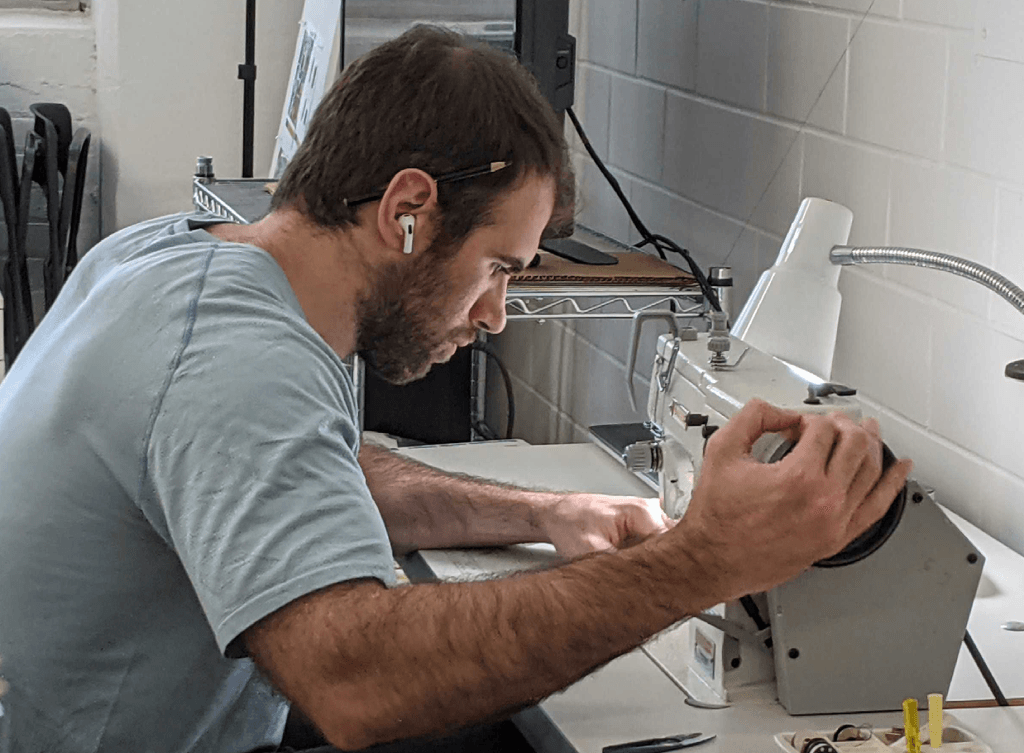

A lot of the time, they happen in parallel. I’ll jump back and forth between 2D sketching and physical prototyping depending on what I’m trying to figure out. But if I’m being honest, there were definitely moments—especially during projects at Interwoven—where I found myself sketching too much. I’d get stuck in the lines, trying to make things look good on paper, but I wasn’t really proving anything. I’d realize I was spending all this time drawing, but not actually learning how something would work in the real world.

That’s why I’ve always loved working in 3D early. I remember being in the studio with muslin draped on a form, sketching right on the body, ripping paper, taping things together. There’s just something about the immediacy of that. You’re not just imagining a form—you’re shaping it in real time, and often that translates right into pattern-making or the next stage of development.

Sometimes, when you’ve got a tight timeline or the project is super function-driven, I’ll skip 2D altogether and go straight to building. I’ll bring a quick muslin or cardboard mock-up to a team meeting and say, “This is what I think it’s doing.” That way, people can touch it, react to it, and we can talk through pros and cons on the spot. You don’t get that level of feedback from a sketch alone.

So yeah, I still sketch—but physical modeling is where I uncover the really good stuff. And often, once I understand how something works in 3D, then I’ll go back to 2D to refine the aesthetics or create a more polished representation. It’s a constant back-and-forth.

Q:

Can you share a specific example of a conceptual prototype that helped solve a problem or clarified your thinking during a project?

A:

The Ninja Frost Valut soft cooler project comes to mind immediately. That one was a wild ride in the best way. They came to us with a super tight turnaround—like two weeks—and said, “We need something functional and fun, and we need to validate the user interaction.” And keep in mind, this was a client with all the resources in the world. They had access to 3D printers, high-end materials, whatever they wanted. But even they knew that to move fast, we needed to get scrappy.

So instead of building out a full-size, high-fidelity prototype, we started with quick, rough mockups—cardboard, muslin, whatever we could use to visualize the structure. It was about figuring out how the top door worked, how the zipper would interact with the opening, how the compartments connected on the inside. They told us, “We want to fit 18 cans and a wine bottle,” which sounds specific but gets tricky once you start shaping the actual space.

That’s the beauty of these early mockups. They let you work within constraints and still explore. You’re building something real enough to evaluate, but flexible enough to change on the fly. We’d hold the model, try different openings, move things around. If we’d started with a polished CAD file or waited on a perfect 3D print, we would’ve lost valuable time—and we probably wouldn’t have caught some of the spatial issues until much later.

So even in a super corporate environment, the quick and dirty models were essential. They gave us clarity, speed, and insight—all things you can’t afford to miss when you’re on a tight timeline.

Q:

Can you give an example of a quick model that taught you something you wouldn’t have learned on paper?

A:

Totally. One of the best examples I can think of actually goes back to the HeroWear Apex exosuit. We were working on the early development of the wearable, and we were designing things like the shoulder straps and leg portions—really important areas for comfort and function. And the thing is, you can look at all the biomechanics research in the world, but until you physically mock something up and put it on a body, you don’t feel the impact of the design.

I remember making these super rudimentary models—muslin straps, cardboard cutouts, foam forms—and just trying things on. One tiny change, like shifting the sternum strap half an inch higher, would totally throw off the balance. It would start pulling back on the upper plate in this weird way, or it would choke you a little if there was any tension. It was a great reminder that the human body doesn’t care what the sketch says—it cares how it feels.

That was especially true when we were testing on different bodies. Something that fit me well didn’t necessarily work on Aybuke or Meghan. We were seeing, in real-time, how much variation there is in anatomy. And we weren’t just looking at fit—we were watching how people used the prototypes. One person would put on a backpack starting with their left arm, another would hoist it from the bottom, someone else would swing it over their shoulder. All of those micro-behaviors matter.

So in that case, the mockups weren’t just about proving fit—they were about revealing differences in interaction, body types, motion, all of it. None of that was visible in the drawings. You had to build it and put it on people. That was the only way to really learn.

Q:

What kinds of materials do you gravitate toward when making these sketch models, and how do those choices shape the way you think through a problem?

A:

It really depends on what I’m trying to solve. I’ll use muslin if I need something that drapes or behaves like fabric, cardboard when I’m looking at form and structure, and EVA foam is kind of the wildcard that I love to use when I need something that does a little bit of everything. That stuff is gold—it can act like a soft shell, a flexible strap, even simulate Velcro depending on how you cut and tape it.

The thing you have to watch out for, though, is that people will take whatever you show them literally. If you’re showing a conceptual prototype to marketing or upper leadership and you use a stretchy mesh just because it looks good or is easy to sew with, they might say, “Oh wow, this feels amazing—we should use this!” And you’re like, “No, no, this isn’t the real material! It’s just here for the mock-up.” So I’ve gotten more strategic over time.

For example, when I was working on the Breg knee brace, I used EVA foam in all these crazy colors—turquoise, lime green, bright yellow—on purpose. If I’d made the models in black, which is what the final product was supposed to be, people would’ve gotten way too literal. But the wild colors kind of divorced the client from the final form just enough so they could focus on what the prototype was doing, not what it looked like.

So material choice isn’t just about function—it’s about communication. It’s about knowing who you’re showing it to and what message they might take away from it. I’ve learned to be really intentional about that.

Q:

What kinds of insights have you gained from building models that surprised you?

A:

So many. One of the most memorable was while working on the Apex exosuit for HeroWear. We were testing strap placements, and even with minimal tension, a small shift in sternum strap height could cause major fit issues. It made us more aware of how anatomical differences—especially between male and female bodies—affect fit. You also learn a lot just by watching how people put things on. No two users interact the same way.

Q:

How did your time at Interwoven shape the way you design and prototype today? Are there any techniques, habits, or philosophies you still carry with you?

A:

For sure. I think the biggest thing that Interwoven gave me—besides hands-on experience—was confidence. Confidence to put unfinished ideas in front of other people and say, “Here’s where I’m at,” even if it’s not polished. That’s a hard thing to do straight out of school. I was so used to trying to perfect everything before I shared it. But at Interwoven, we moved so fast. You didn’t have time to obsess. You had to get your idea out there, test it, talk about it, and then move on to the next iteration.

I remember the first time Rebeccah handed me a piece of EVA foam and said, “Just mark it up. Make a model.” And I was like, “Wait—what?” But once I did it, it unlocked something. It gave me permission to try things and not worry if they were ugly or halfway done. That mindset—that a rough idea is still a valid idea—has stayed with me. I carry that into everything I do now.

At Interwoven, we prototyped constantly. Blue-sky concepts, tech that didn’t even exist yet—we still made physical mockups to explore layout, user interface, ergonomics. Whether it was figuring out battery placement in a pet harness or mapping electronics onto soft goods, we always built first, then refined. That method taught me how valuable foam, muslin, and tape can be.

So even now, when I’m working at a much bigger company, that habit of diving in, getting hands-on early, and iterating fast is something I always go back to. It’s fundamental.

Q:

Conceptual prototypes aren’t always easy for clients or stakeholders to understand. How do you communicate their value without people taking them too literally?

A:

That’s such a good question—and it’s a challenge for sure. I think the biggest thing is knowing your audience. You have to anticipate what people are going to expect based on who they are and what kind of background they’re coming from. If you’re dealing with a huge corporation, they might be used to seeing fully 3D-printed, sanded, spray-painted mockups. That’s their norm. But someone else might be totally fine with cardboard and tape if it helps them understand the idea.

What I try to do is build in smaller checkpoints. Instead of waiting for a big Phase 2 presentation where everything’s supposed to be clean and “done,” I’ll push for a mid-phase touchpoint. It gives you a chance to say, “Here’s where we’re at—we haven’t spent too much time or money yet, but we’re getting important feedback now so we can steer in the right direction.” That sets expectations early and helps people focus on the ideas, not the finish.

Another trick I use is playing with scale and color. If you build something small, or in colors that clearly don’t belong in the final product—like making a knee brace mockup in bright turquoise and neon yellow—people immediately understand that it’s not final. It helps create that separation, so they look at the concept, not the aesthetics.

And sometimes you just have to say it directly: “This isn’t a final product. This is about exploring function, interaction, or layout.” That helps shift the mindset. The point is to open the door for feedback—not to get approval on a finished design.

Q:

In what ways does physical modeling—taping, folding, building—inform your digital work, and vice versa? When do you bring CAD into your process?

A:

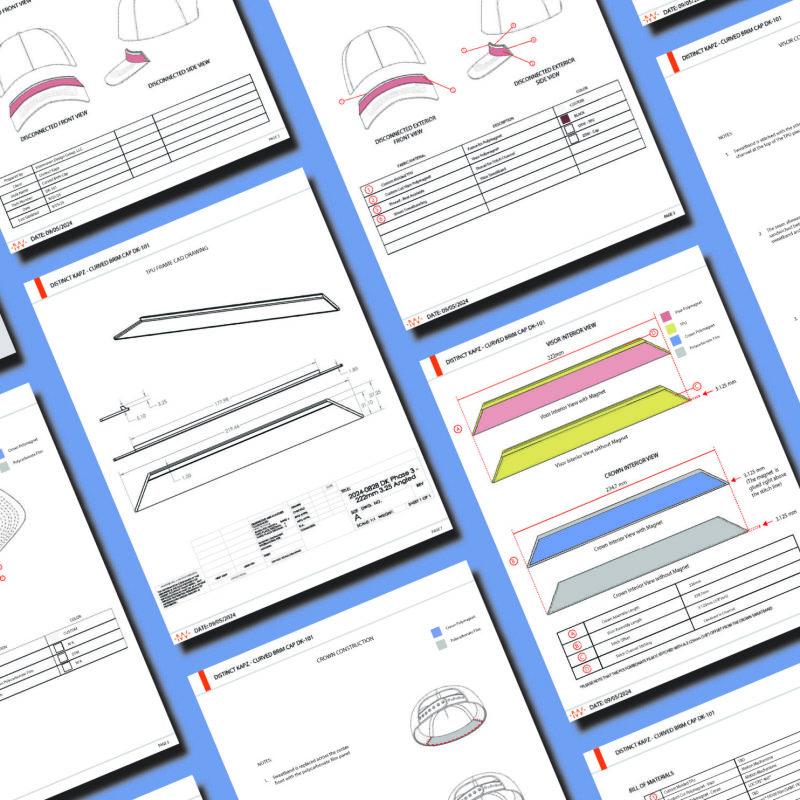

I think physical and digital work are more intertwined than people realize. For me, they constantly inform each other. If I’ve built something to scale—like a muslin vest or a foam form—I’ll take photos of it and bring those into Illustrator. I might drop the opacity down and sketch over it. Or I’ll use it as the base for a tech pack, especially if we’re moving into a pattern-making phase.

Sometimes I’ll scan the flats of a muslin build and start drawing from there. That becomes the foundation for my Illustrator files or even for 3D modeling. And then as you start building in CAD, that’s when you find the real-world limitations—like, “Oh, we can’t mount this piece the way I thought,” or “This part is interfering with another component.” It’s like a back-and-forth conversation between the physical model and the digital file.

If you jump straight into CAD without building anything first, you miss so much nuance—especially around ergonomics and body interaction. The screen gives you precision, but the shop gives you truth. And once you have something physical, even a rough version, it makes your digital work smarter and more intentional.

Q:

What’s your take on failure in the prototyping process?

A:

Failure is 95% of it. You build quick mock-ups, find out what doesn’t work, and share them anyway. At Interwoven, we’d make 10 different models and walk through them as a team. Even if three of mine failed, someone else might spot something worth carrying forward. That back-and-forth was always valuable.

Q:

Final question: What advice would you give a young designer about sketch modeling?

A:

Get up from your desk. Go to the shop. Talk to people. Learn how things are made. And most importantly—don’t be afraid to fail in front of others. That confidence builds with time. Every mock-up, even the rough ones, teaches you something. And you never know who might see something in it that you missed.

—

Check out the rest of our Spotlight series to hear more from leaders in the design industry. Sign up for our newsletter and follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn for design news, multi-media recommendations, and to learn more about product design and development!