Rebeccah Pailes-Friedman&Aybüke Şahin on Bridging Hard and Soft Goods in Industrial Design

For this Spotlight conversation, Interwoven founder Rebeccah Pailes-Friedman sits down with Aybüke Şahin, a Senior Industrial Designer who recently marked her fifth year with the studio. What begins as a casual conversation quickly turns into an expansive dialogue on what sets soft goods apart from traditional product design, why prototyping with fabric requires intuition as much as tools, and how the studio’s hybrid expertise shapes innovation across consumer, medical, and lifestyle categories.

In this rare peer-to-peer exchange, Rebeccah and Aybüke open up about shifting user expectations, navigating clients with very different design cultures, and how understanding human behavior continues to shape the way Interwoven brings ideas to life.

RPF: Okay, let’s get started. First, I just want to say thank you for taking some time out of your busy day to have this conversation about soft goods.

AS: Yes, absolutely—this is fun. We’re usually deep in projects, so it’s nice to step back and talk about how we actually approach the work.

RPF: So, to begin with, how long have you worked here now?

AS: It’s been a full five years.

RPF: Amazing. It went by fast.

RPF: What do you think is the biggest difference between traditional industrial design and the kind of soft goods work we do here at Interwoven?

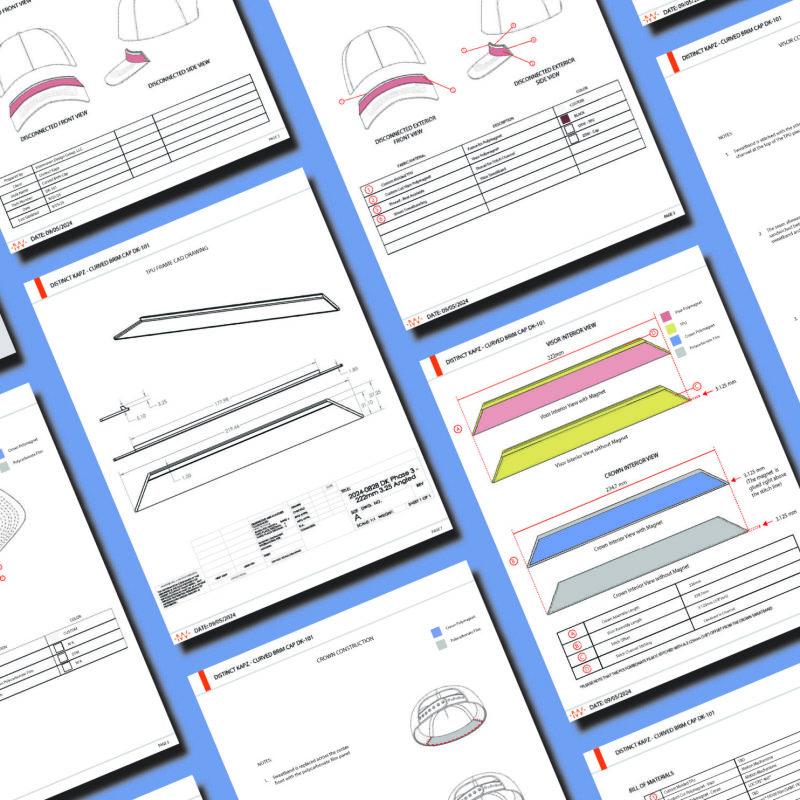

AS: I think the way we think about problems—or not even problems, but the conditions that come with softer materials like fabrics—are really different. In traditional hard goods, it’s sometimes easier to imagine things on paper or in CAD with rapid prototyping. But with fabric, we can imagine something and then it ends up behaving completely differently when we actually prototype it. I find there’s more back-and-forth, more revisions, especially in how components interact with softer materials.

RPF: I know exactly what you mean. Textiles behave differently than any other material. When you’re working in plastic or metal, the sky’s the limit—whatever you can CAD, you can produce. But with textiles, you’re limited by how the material behaves. You have to understand the material’s behavior in order to design something effective.

AS: So Rebeccah, in your expertise—and you’ve been in the field for quite some time now—how do you think user behaviors in relation to wearables or soft goods shape the way we prototype and test?

RPF: I think it all comes down to people’s behavior—how they move, how they feel comfortable. If something is uncomfortable, it literally changes the way you behave. Think about how dress clothes used to be the norm. Who wants to wear a dress shirt or a blazer now? You can’t move your arms, you can’t breathe—it’s physically restricting. I think that shift in tolerance—people just aren’t willing to be uncomfortable anymore—is huge. Understanding human behavior and translating that into the products we design is a core part of what we do. And you really saw that shift during the pandemic. People got used to wearing comfortable clothing at home and now they don’t want to go back to discomfort. That changes how we think about designing soft goods.

AS: I totally agree. And soft goods is definitely growing as an industry. When we first started doing this, there weren’t many people in the space who did what we do. Now there are a lot more. There’s more research, more product development, and more technologies popping up that incorporate wearable or soft systems.

RPF: Yeah, and it all comes back to how people want better experiences—something that’s easier to use, something that gives them value in their daily life.

AS: Exactly. But with soft goods, it’s not that simple. You can imagine something perfectly in your head, or even draw it out precisely, but the moment you start working with the fabric, it surprises you. Textiles behave in really unique ways. They stretch, fold, collapse, resist—things you can’t always predict until you physically make the piece.

RPF: Yes! With textiles, behavior is everything. When you’re designing in metal or plastic, you’re only limited by the constraints of your tooling or manufacturing method. But with textiles, you’re also designing within the behavior of the material. If you don’t understand how it drapes, stretches, or responds to tension, you’re lost.

AS: That’s why I think our design process here often involves more back-and-forth between ideation and physical prototyping. There’s more revision, more iteration, because the material itself is such a big part of the equation.

RPF: It’s funny—sometimes the constraints of fabric can be frustrating, but they also force you to get creative. And over time, we’ve built our own internal “library” of material behaviors and techniques. It’s experience, but also intuition.

AS: And it’s collaborative. We learn from each other all the time here—about materials, patterning, construction, testing. It’s not just about getting a good idea out; it’s about translating that idea into something functional, wearable, and manufacturable.

AS: So building on that—let’s talk about our methodology for designing comfortable, inclusive, and high-performing soft goods?

RPF: It’s not just about softness or flexibility. It’s about how products move with your body, how they accommodate different sizes and shapes. Designing for comfort now means understanding biomechanics, posture, and even emotional cues.

AS: It’s part of why soft goods are growing so quickly as a category. There’s more demand, more innovation, more cross-pollination between fashion, health, tech, and lifestyle. When we started doing this work, there weren’t a lot of people combining design and engineering in this way. Now it’s really taking off.

RPF: Another thing I think sets our work apart at Interwoven is the way we merge soft and hard components. I’ve always been drawn to that crossover, and it was one of the reasons I was so excited to bring you onto the team—your background in hard goods really expanded what we could do.

AS: Thank you! I’ve really enjoyed that part of the work—figuring out how to integrate structural components like electronics, batteries, or sensors into wearable products without compromising comfort.

RPF: There’s a long tradition of wearing textiles, of course—clothing has been around forever—but there’s not a long tradition of integrating textiles with technology. It’s still relatively new. We’ve been on the forefront of this field for over 15 years.

AS: That’s what makes this work so exciting. Depending on the product category—whether it’s medical, travel, lifestyle—we have to adapt our approach. The way we combine soft and hard materials changes depending on regulatory standards, user context, durability needs, even washability.

RPF: We’ve developed a methodology, but it’s flexible. Every project brings new questions. And our experience becomes this evolving library that we draw from—but never apply in exactly the same way twice.

AS: We’ve worked on projects where even the smallest detail—like the orientation of a seam or the coating on a zipper—can make or break the user experience.

RPF: Yes. And I think this is especially true in health and medical products. More and more, users expect those products to offer experiences, not just functions. They want something intuitive, comfortable, attractive—not just technically correct.

AS: That was a big part of our work on the Even Adaptive lingerie line. It needed to function for people with limited mobility, but it also had to feel empowering. It had to look good. It couldn’t just scream “assistive device.”

RPF: Exactly. It had to be part of a person’s daily life, not a constant reminder of their limitations. And I think the final result really achieved that. It wasn’t just helpful—it was beautiful. And it ended up being useful for more people than we originally imagined.

AS: That’s one of my favorite kinds of outcomes: when inclusive design leads to better design for everyone.

RPF: Let’s switch gears for a moment. Over the years, we’ve worked on all kinds of products, but one of the more recent launches was the SharkNinja FrostVault cooler backpack. What did you find particularly interesting—or challenging—about that project?

AS: A lot, actually. First, working with the SharkNinja team was really interesting. Their internal process is very fast-paced, and different from ours. They had multiple teams working on different parts of the product simultaneously, so we weren’t always privy to the full picture. That made collaboration a little tricky sometimes.

RPF: Yes, I remember feeling like we were coming in to solve parts of a puzzle, but we weren’t always sure what the final image would be.

AS: Exactly. That said, I really enjoyed the challenge. From a product standpoint, it was technically fascinating. We had to think about waterproofing, insulation, internal organization—all while making it wearable and comfortable.

RPF: And even though the exterior was technically textile-covered, it wasn’t a soft good in the traditional sense. Most of the bag was rigid, with plastic-coated fabric to repel water. The true soft goods component was the strap system.

AS: That’s where we had the most impact—designing for fit and comfort across a range of body types. I remember testing on you and Anthony and realizing how much the same strap design could feel completely different depending on the user.

RPF: It was a real lesson in anthropometrics. And it goes back to that idea of merging hard and soft—making something that performs structurally but feels good on the body.

AS: There was also the challenge of sealing off the internal compartments. One section needed to stay cold and insulated, while the upper section needed to be separate for dry storage. Getting that internal seal right—without adding bulk—was no small feat.

RPF: It was a tight balance between design, engineering, and user comfort. But the final product is really strong, and I think our collaboration with their team made it better.

RPF: One thing I’ve noticed is that we often partner with teams who share similar skills to us—but not our specific expertise. We’re frequently brought in to bridge gaps, especially when it comes to human interaction and wearability.

AS: Yes, and I really enjoy that. Sometimes we work with an engineering team that knows everything about mechanics, but hasn’t thought much about how something will actually feel on the body. Or we work with an industrial design team that hasn’t dealt with textiles before.

RPF: It’s a good reminder that design is never one-size-fits-all. It’s always collaborative, always context-driven.

RPF: Okay, time for a fun question: What’s one soft goods or wearable product you absolutely can’t live without?

AS: I have two! First is my sleep mask. It’s simple, but I love it. It covers my eyes and has a puffy filling—not just dense foam. The headband is really soft and comfortable. I use it every night.

RPF: That’s a good one. And the second?

AS: My dog’s harness and leash! I’ve gone through so many versions to find the right one—something he’s comfortable wearing, that I can easily use, and that doesn’t mess up his fur. One of them even made him limp because of how it applied pressure to his shoulder. I didn’t realize a harness could do that until I switched to a different one and the limp disappeared.

RPF: Wow. That really shows how critical good soft goods design is—even for pets. Pressure distribution, material selection, adjustability—it all matters.

AS: It does. It’s made me hyper-aware of how even small design choices can have huge consequences for comfort and safety.

RPF: That really brings it full circle. What we do here—whether it’s for people or pets, medical or lifestyle—comes down to paying attention. To behavior, to comfort, to context.

AS: Exactly. And honestly, this has been really nice. We work next to each other every day, but we rarely stop and have a full conversation like this.

RPF: I know! This was so fun—and a great way to mark five years. Here’s to the next chapter.

—

Check out the rest of our Spotlight series to hear more from leaders in the design industry. Sign up for our newsletter and follow us on Instagram and LinkedIn for design news, multi-media recommendations, and to learn more about product design and development!